Getting a start in agriculture at ten years old, Iowa Learning Farms farmer partner Devin Davis understands the importance of preserving the land. When he became a key decision maker on his family’s Warren County farm in 2019, Devin pushed to implement practices such as no-tillage, cover crops, and buffer strips. With a goal of expanding conservation practices on his family’s 2,000 acres, Devin does all he can to benefit his land while remaining profitable.

While his immediate family started farming in 2000, Devin has an agricultural heritage that runs eight generations deep. As a child, and throughout his teenage years, he helped where he could. Following his graduation from high school, Devin earned his degree in political science from the University of Northern Iowa and went on to Drake Law School. After passing the Bar Exam in 2015 and receiving his associate degree at the Culinary Institute of America in 2019, Devin returned to Warren County. Upon his return in 2019, Devin took on a leadership role on his family’s farm. Currently, he farms full time in addition to being a part time lawyer in Des Moines.

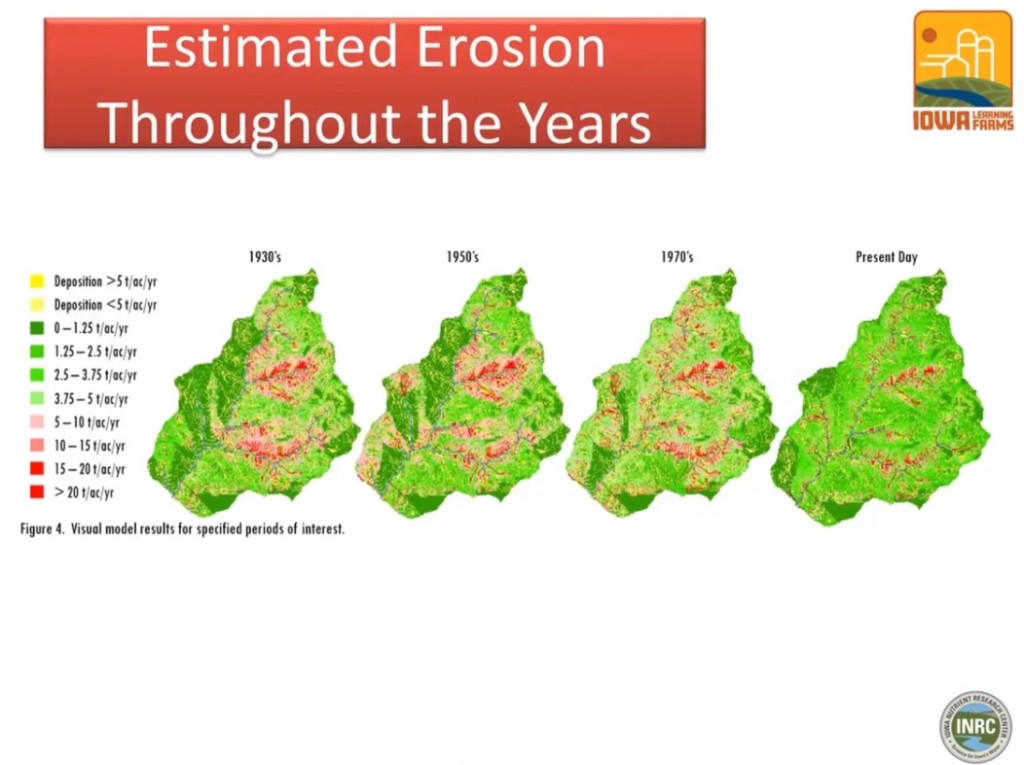

Conservation can be seen in many forms across Devin’s land. As a farmer and a lawyer, he understands the value of time. Because of this, nearly all his acres are no-till. This reduces the time spent making multiple passes in each field. In addition, Devin currently plants roughly 300 acres of cover crops. His hope is to increase the number of acres planted into cover crops through the Conservation Stewardship Program. Nutrient management is another important issue for Devin. By only applying nitrogen in the spring, he hopes to reduce losses and improve the effectiveness of his application. This year, Devin also attempted to double crop winter wheat and soybeans. The wheat was harvested in July and sold as grain, and soybeans were planted immediately after. Due to the lack of rain, he is unsure how well the soybean crop will yield but he hopes this experiment could lead to opportunities in the future. Other practices on Devin’s farm include buffer strips on field edges and controlled traffic patterns to reduce compaction.

Conservation practices don’t come without their challenges. One challenge Devin noted is the tradeoff of short-term and long-term gains. It’s common to focus on the short-term goals such as reaching record yields. In addition to increased yields, Devin’s larger goal is to gain the long-term benefits of his conservation practices through improved soil health and water quality. As time goes on, he hopes to see people hold the idea of maintaining the health of the land as high as maintaining crop production.

Despite challenges, Devin takes great pride in all the pieces that go into being an Iowa farmer. “I don’t think there’s any other job in the world that requires such a broad, diverse set of skills and abilities.” Devin notes a farmer has to be a mechanic, agronomist, weatherman, and a salesman all in one. Being able to constantly learn has motivated Devin to keep looking forward to new opportunities and continue, “to do right by our families, right by our communities, and right by our land.”